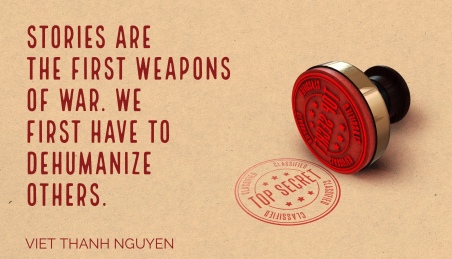

On his visit to Houston in November, as part of the Inprint Margarett Root Brown Reading Series, Viet Thanh Nguyen described his overarching projects as a writer. First, to center the voice of the refugee in the United States. Second, to examine the ways narratives influence memory. Nguyen asserts that we must change the publishing industry so we can tell, hear, and listen to other stories. In fact, it is worth watching the full recording of his talk.

In his book The Refugees, Nguyen utilizes short story to tell a complicated, nuanced, heart wrenching, stoic, and beautiful set of tales that center the lives of refugees. While many of these fictional stories center the lives of refugees who fled Vietnam, Nguyen challenges the definition of refugee. Certainly those who flee war, violence, and famine are the traditional way we think of refugees. These are centered in this short story collection.

In his book The Refugees, Nguyen utilizes short story to tell a complicated, nuanced, heart wrenching, stoic, and beautiful set of tales that center the lives of refugees. While many of these fictional stories center the lives of refugees who fled Vietnam, Nguyen challenges the definition of refugee. Certainly those who flee war, violence, and famine are the traditional way we think of refugees. These are centered in this short story collection.

However, Nguyen also seems to pose the question of how we might be refugees from ourselves. How are we all refugees of history? How do we become refugees from our memories? How does narrative and story function as a shape-shifting force in our lives – and how can we challenge conventional narrative tropes of our culture, and those we tell ourselves?

These are weighty, difficult, but beautiful stories that unfold with Nguyen’s profound ability to shape language and narrative arcs in ways that fully immerse a reader. Throughout reading this book I was left stupefied – almost suspended in limbo with the rawness of life these stories evoke. I felt absorbed in the complexity of text and the stories – though it is difficult to put into words exactly how this feeling manifests itself. There is an intensity of the human experience in these narratives that lends a reader to recognize that the human experience is an experience of being a refugee. From what and whom are we fleeing?

War and Fatherhood

The most striking theme in these stories is that of the absent-present father. Sadness, deception, lies, violence, and isolationism surround the stories of fathers in this book. As all the fathers in the text are impacted by the Vietnam War, Nguyen is using these stories to explore the inter-generational impacts of the conflict and its fallout on the role of fatherhood. Sometimes Nguyen subtly articulates this fallout, as in the story “Fatherland,” when Phuong notes her father “wore his sadness and defeat in a paunch barely contained by the buttons of a shirt one size too small for him” (p. 188).

At other times, violence is explicitly centered. Thomas’ father, in the story “Someone Else Besides You,” not only exerts physical violence on his sons (through forcing them to run until they vomit, for instance), but also emotional and psychological violence on his wife and sons (having mistresses or advancing notions of toxic masculinity). This violence also manifests itself when Thomas’ father slashes the tires and busts the windshield of Thomas’ ex-wife’s car. In this story, the absent-present father and intergenerational damage of war also become centered. Thomas, so fearful of becoming like his father, refused to have a child with his ex-wife, which ultimately led to their divorce. The reconciliation near the end of this story – though beautiful – also raises questions about fatherhood, responsibility, and disrupting intergenerational cycles of violence and war cast upon men in the role of fatherhood. There are many other examples of the impacts of war on fatherhood throughout the narratives.

Forgetting the Body

Throughout the text, Nguyen eloquently uses language to center the body – although these bodily images appear to vacillate between extremes – petiteness and almost overpowering physicality. The characters across these stories all have unique engagements with forgetting or coming into appreciation of their bodies. The body seems to become detached in these stories. The characters lose touch with their own bodies, their own sexuality, and their ability for human connection. In at least one case, the invoking of prosthetic limbs actually exerts physical detachment as well.

In “The Other Man,” Liem comes into his queer sexuality, although queer sexuality is clearly devoid of connection to love in this story. Sex becomes about pure physicality, not raw or heartfelt emotionality. The body becomes a vessel to be used for physical pleasure, but must be separated from emotional attachment. It is heartbreaking. This appears as a theme in other stories throughout the text, as well. In “Black-eyed Women,” the narrator seeks to forget her body altogether, retreating from sexuality and emotionality following her near rape while fleeing Vietnam. In “Fatherland,” Phuong comes to discover her sexuality upon receiving the gift of lingerie from her half-sister, though she rejects any potential sexual and emotional attachment to another individual.

In perhaps the most poignant, heart wrenching, and beautiful of the stories in this collection, “I’d Love you to Want Me,” Mr. Khanh actually loses his mind. This is a story of dementia – and Nguyen poignantly and poetically takes readers through the cycle of losing one’s memories and control of one’s bodily functions. Here again, radical displays of bodily physicality are juxtaposed. Mr. and Mrs. Khanh’s son, Vinh, is described as overly-muscular: “The edge of her hand could have fitted into the deep cleft of her son’s chest, and her thighs weren’t quite as thick as his biceps” (p. 104). This muscular corporeality is starkly contrasted to the frailty of their own bodies. These juxtapositions of the body throughout the stories are striking.

Even in “The Transplant,” a story about Arthur Arellano and his unexpected discoveries of the body, center this theme. In this story, Arthur is forced to have a liver transplant, his original liver failing due to hepatitis. Though healthy following the transplant, the narrative follows these themes of bodily rejection: “the liver throbbed inside him, the size of a first-trimester fetus, forever expectant but never to be born, calling for his acknowledgment, gratitude, and love the way it constantly had done in the weeks after the operation” (p. 92). This fear of rejection extends, again, to physical human contact. At one point in the story, Arthur’s wife Norma issues a directive: “‘Do not touch me, and do not come close to me’” (p. 82).

Belonging, Remembering, and Forgetting

Above all, refugees in these stories struggle with belonging. Each character seems to question where they fit. Should they continue fighting to return and save the homeland, as in “The War Years?” Intergenerational questions rise and flare in these stories. There is a boiling kettle-pot of tension in “The Americans,” a story about biracial, binational identity. How do the children of Americans who fought the war – bombing and napalming Vietnam – return to make amends for the sins of their parents who tortured the land and left it for ruin? This story is also a question of whether one born in a country of great sin (in this case, the United States) must become a refugee from that country of origin in order to deal with its moral and ethical failures.

The story of the refugee is one of what we should remember, and what we should forget. In the epigraph to the text, Nguyen cites “A German Requiem,” noting that what haunts us in our lives is that which we want to forget but can’t. One way we seek to forget is by spinning new narratives – and this book is chucked full of tiny phrases Nguyen pokes at the reader to make us interrogate this question of narrative, remembrance, and forgetting. “We had no belongings except our stories” (p. 7); “we all tell ourselves what we want to hear” (p. 75).

The story of the refugee is one of what we should remember, and what we should forget. In the epigraph to the text, Nguyen cites “A German Requiem,” noting that what haunts us in our lives is that which we want to forget but can’t. One way we seek to forget is by spinning new narratives – and this book is chucked full of tiny phrases Nguyen pokes at the reader to make us interrogate this question of narrative, remembrance, and forgetting. “We had no belongings except our stories” (p. 7); “we all tell ourselves what we want to hear” (p. 75).

And, in what I think is the poignant of these passages in the text on the power of narrative, reading, and remembering:

She wondered what, if anything, she knew about love. Not much, perhaps, but enough to know that what she would do for him now she would do again tomorrow, and the next day, and the day after that. She would read out loud, from the beginning. She would read with measured breath, to the very end. She would read as if every letter counted, page by page and word by word. (p. 124).

Join us at the Inprint Book club, Sunday February 11 at 4PM, as we change the narrative, remember, and discuss Viet Thanh Nguyen’s beautiful exploration of the human condition.

Why can’t we have you writing reviews for The New York Times and the other prestigious publication? Yours have so much more substance and avenues for further reflection. I printed this out to discuss with you and the group tomorrow. Thank you for devoting your limited time to enrich our lives and enlarge the experience of Nguyen’s work.